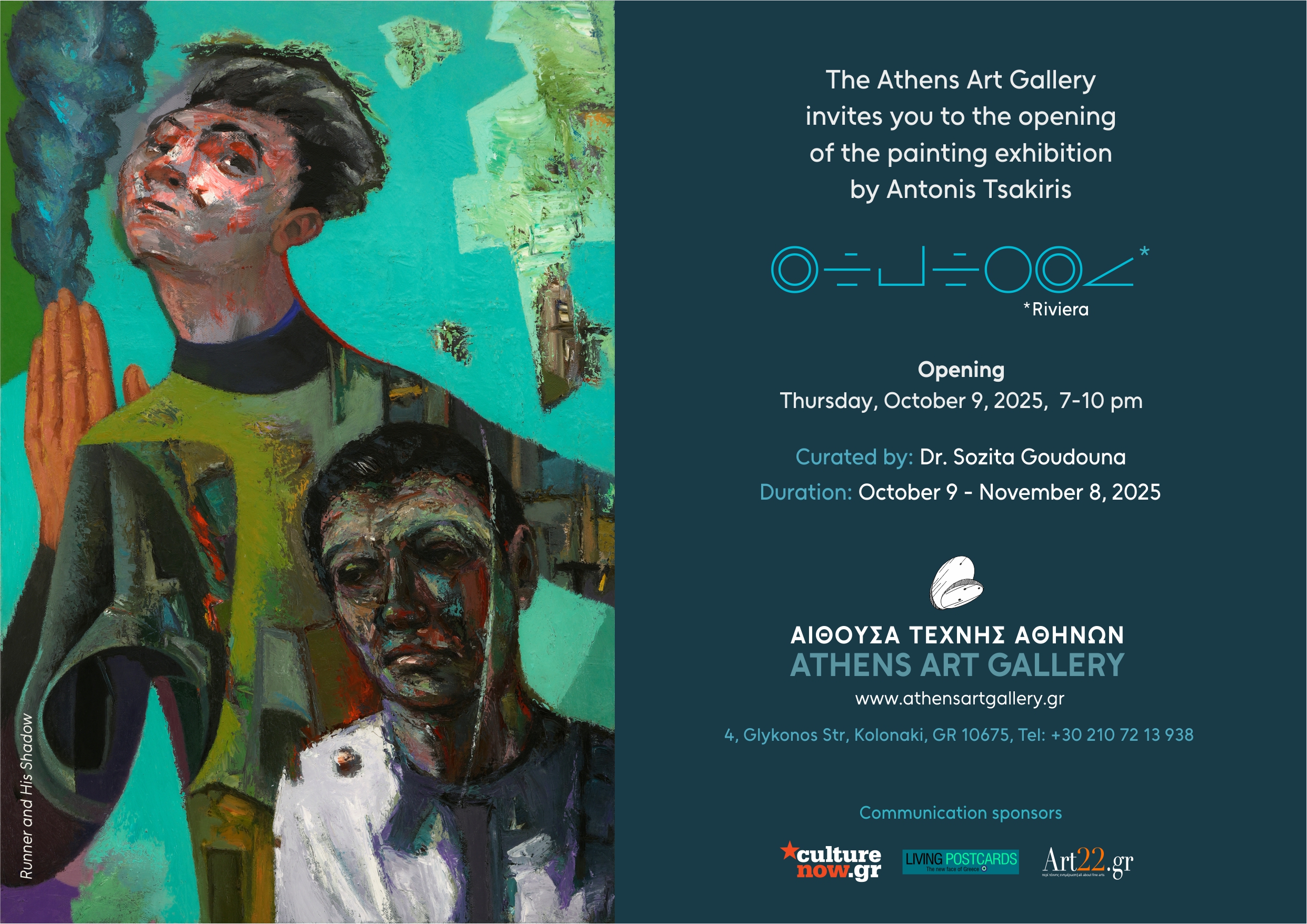

As he prepares for his upcoming exhibition, painter Antonis Tsakiris opens up about his creative process, the ideas behind his new body of work, and the personal and artistic journey.

Was there a defining moment when you realized you were an artist?

Although it might seem romantic, I don't think there is a single specific moment to realize what we want to do. I believe that something that exists naturally within us gradually finds its way to the surface, to the conscious mind, until it becomes undeniable and clear.

Probably small, scattered occasions nourish this underlying feeling, which grows within us, and once it is big enough, it wants to leave the house and become a painter, scientist, football player, or whatever it is.

There are moments. Some are magical. I remember the first time I felt that the work I was creating was good. I just knew it was complete, that there was no point in adding or removing anything.

I felt as if I were in a museum, looking at a painting that I liked. Or even earlier, in the beginning, when I added the touch of white gloss to the eye of a girl's portrait and thought that it seemed to come to life. And more.

But I was already painting, probably following whatever came most naturally to me without explanations.

Your new exhibition ''Riviera'' is sparked by a memory fragment — an evening walk under the summer full moon in the Athens Riviera. Can you tell us more about that moment and how it became a starting point for this body of work?

An image, like many others, kept returning persistently, as often happens with events we have experienced or with people we have interacted with. The interesting thing in this case was the addition of the wrecked car on the beach.

This mental collage was the key, the intrigue of the thought. And more than the image itself, the reason why these two were connected: the full moon that silvered the sea on the Athenian Riviera and death.

Since my painting is mainly human-centered, I was intrigued by this exploration and ultimately by its depiction. Always through the filter of the act of painting. From the zero of the blank canvas, where everything is possible, to the colors, the forms, and the farewell to absolute freedom.

Your work has this poetic, instinctive feel — almost like a response to how fast and intense the world is these days. How do you turn those kinds of feelings into something visual when you’re painting?

This is the magic of Art. Its metaphysical existence. When I paint, I am someone else, or, to be more precise, it is as if a strange, handsome guy enters the studio, silent, expressionless, determined, almost robotic; he doesn't glance around at all, goes to the canvas, does his thing, and leaves without exchanging a look or a word. I never see his face. I wake up in the morning, go to work full of curiosity to see its progress.

The wonderful thing is that even now, after so many years of painting, he keeps coming. I thought about leaving him something to nibble on, or a glass of wine, but I am sure he wouldn’t touch them.

Memory, instinct, and imagination seem to be central themes in your work. How do you navigate the balance between personal experience and collective memory in your paintings?

As citizens of the world, what happens on the planet—and there is much—affects us whether we like it or not, whether we admit it or not. Everyday life is intertwined with personal temperament, with each person's deepest emotions, and this mix is what makes people as we know them or as they appear.

The matter of creation is that you have the ability to express the effects of these stimuli, to translate them into images, writing, music, etc.

Creators are at the same time lucky, because they have a way to externalize this mixture, but also more exposed, when they are honest in what they do. 'Dancers,' as Kundera calls those who expose themselves. In any case, the truth is the only map that leads to some happy clearings.

Your visual language is described as bright and simple, yet your compositions explore complex narratives. How do you use color and geometry to express emotional or psychological depth?

The hardest part when I paint is not taming the surge of emotions, but organizing them in a way that tames the chaos. Balances are difficult, in composition, in the essence of the work.

Over time, I realize that a geometric foundation leads me to a sense of stability upon which I can place whatever I want, no matter how flamboyant or erratic it is.

Geometry becomes a foundation. I paint what I am. I have naturally intense emotions, and I often experience situations intensely. It is wonderful to understand that the use of geometry in my paintings helps me in many ways, even in my life outside of them.

Is there a particular painting in this exhibition that feels especially personal to you?

In this section, in 'Riviera,' all the works are equal pieces of the puzzle. They form a set of points of parallel everyday life at the same time that some car becomes an amorphous mass by the sea.

A tragedy unfolding here, someone returning home from work by bus there, nearby a butterfly/driver, a runner with his confused shadow, the observer, in the theater's cloakroom in the next block, where, along with their coats, all the creatures of the night and the sea leave their souls, and other such simple, everyday things. It is a world with the beautiful and the ugly, the many and the few.

Can art be a tool for social change?

Yes, of course, as long as it is not, let's say, politically driven. Then I consider it to be distorted; it doesn't have the same impact. Art in itself cannot change the world. It can change the artist.

However, it has the power to provoke prick in people's consciences. I will never forget when I visited a friend at her home, back when I was still eagerly absorbing everything related to painting.

She had in her living room a life-size reproduction of the work "Portrait of Lounia Tchehovska" or "Woman with a Fan" by Modigliani.

The woman's gaze in the painting was exhausting; it followed me for days, and I still remember how I felt when I first saw it.

It was a presence in the flesh.

Let us remember that after the terrible September 11, when the U.S. Secretary of State under George W. Bush, Colin Powell, made statements in 2003 at the United Nations offices listing the reasons why the United States needed to invade Iraq, there was behind him a copy of Picasso's "Guernica," covered with a sheet.

This happened according to Powell's own instructions, as it was considered that the depiction of destruction and war would be inappropriate for a speech that would present the need for a war.

Do you find inspiration in other art forms like music or literature?

Yes, of course, the arts communicate with each other and mutually inspire each other.

While painting, a musical piece comes to mind; while reading, the words are visualized as you hear the sounds of the stories with your imagination, etc.

Art is salvational. It so happens that I play music; at one time, I used to compose songs and music, I wrote for television, I played in small clubs, and I met amazing people. I have a twelve-string guitar in my studio, and very often, in between painting, I make sure to keep it warm.

Music, especially, is the highest art. I cannot imagine life without it.

What advice would you give to young or emerging artists who are trying to find their own voice in the art world?

I get the impression that a certain affectation comes out unintentionally when I have to give this kind of advice. I think, however, that an artist's compass should always point to the truth. Combined with hard work.

If you are honest with yourself and have an objective awareness of reality, even to a cynical degree, then you have a chance to create something truly exceptional.

The deeper your feet are planted in the ground, the higher you can fly.